Do you want to take your scientific writing skills to the next level?

As a scientist, your career depends primarily on your publications. But publishing in high-ranking journals is a tough game. So, to put all the odds in your favor, you must first learn what makes for excellent scientific writing. In this guide, you’ll learn everything you need to know to write an article that will hook your readers and get you into the best journals.

Table of content

- 1. Tell a story

- 1.1. Why should you care about storytelling in scientific writing?

- 1.2. What makes a good story?

- 1.3. Scientific storytelling

- 2. Structure your paper

- 2.1. The IMRaD structure in scientific writing

- 2.2. The shape of an hourglass

- 2.3. A symmetrical structure

- 3. Structure your paragraphs

- 4. Improve your style

- 5. Conclusion

1. Tell a story

“Whoever tells the best story wins” Michael Weber

Would you like to know the magic trick to captivate the readers of your paper? You need to tell them a good story. Stories aren’t just on Netflix and in Harry Potter books; they’re an integral part of the scientific articles you write. In the next few sections, I’ll explain why and how.

1.1. Why should you care about storytelling in scientific writing?

It’s human nature to be fascinated by stories. You’ll find them in every culture, from hunter-gatherers recounting the adventures of their ancestors around the campfire to modern viewers dying to know who killed Joffrey in Season 3 of Games of Thrones. But why do we love stories so much?

1.1.1. Stories create vivid emotions

If you doubt that stories can trigger strong emotions, I just have one argument: Watch the movie “Dancer in the dark.” If you haven’t seen it, I don’t want to spoil it for you, but I’m telling you, you’re going to cry your eyes out (and you may even throw up).

Actually, I also have a scientific argument. Research shows that stories exert strong effects on our brains and bodies. For instance, neuroeconomist Paul Zak from Claremont Graduate University has shown that watching dramatic stories increases heart rate, changes breathing patterns, facilitates skin conductance, triggers the release of stress and attachment hormones, as well as brain activations associated with empathy and distress.

You can watch this video to better understand the effects of storytelling on people’s brain, body and behavior.

1.1.2. Stories capture our attention

Stories capture our attention by creating tension.

This tension is elicited by a challenge that the main character faces. More or less consciously, we long for the hero to overcome this challenge, and we continue reading until this tension is resolved.

1.1.3. Stories make us take the perspective of the narrator or of the main character(s)

When we read a story, we start to see the world through the narrator’s or characters’ eyes.

This process is so powerful that Uri Hasson, a neuroscientist at Princeton University, has shown that the brains of the listeners synchronize with the narrator’s. The listener vicariously shares the experience of the narrator and, thanks to this process, understands better what he or she explains.

1.1.4. We remember stories

We remember stories way better than any other kind of information. I bet if you were to retain only one thing from this post, it would be one of the stories you will read (yes, there are several to come :-).

Thus, writing information in the form of a story makes it directly more appealing. However, storytelling in scientific writing is more than just a nice package to share your data with the world: Good research tells a good story. Why is it so? To understand this point, you first need to understand what is a story.

1.2. What makes a good story?

Scientific articles tell a story. Therefore, to understand what makes a good paper, you must first grasp what makes a good story. So in the next few sections, we’ll take a little detour in our science writing journey to discover the elements of a story. I know this may seem off-topic, but trust me! To become a master at scientific writing, you must first learn to tell stories.

What you need to know about stories is that they always unfold following the same pattern (except in Christopher Nolan’s movies because why do simple when one can be complicated). I’m going to repeat this information because it’s VERY IMPORTANT!!! Stories always unfold following the same pattern. You may have never noticed it, but once you know about it, you will see it everywhere, and you will have gold in your hands. So what is this precious pattern?

Stories encompass five elements:

1. An opening on the characters and setting

2. A challenge

3. An action

4. A climax

5. A resolution

Let’s take an example: The three little pigs.

1.2.1. Opening: Characters and setting

Stories begin with an opening that introduces the character(s) and the setting. Everything you need to know about the main characters is in this opening.

The opening sets the tone for the story. Indeed, the opening creates a first impression that has a strong impact on readers and leads them to decide whether to continue or not. Thus, to capture the readers’ attention, the opening should depict interesting characters. For children, what could be more appealing than three little pigs?

1.2.2. Challenge

Once we are hooked by the characters comes a challenge that they must overcome. The challenge of a story is essential because it creates tension in readers, a tension that motivates them to continue reading.

For instance, in a detective movie, the challenge is to solve a murder; in a romantic comedy, it is to find happiness in love; and in an action movie, it is to put the bad guys out of action. For our three little pigs, the challenge is to survive on their own in the world, starting with putting a roof over their heads.

Talking about challenges, a few months ago, I did something I’m not proud of. I was watching a movie that was slow and, frankly, a little boring for my taste. But I was hooked by the challenge. I wanted to know how the main character was going to handle her unwanted pregnancy. So I fast-forwarded the movie to the final resolution, and when I had figured out how it ended, I turned off Netflix and went happily back to my life. The tension I experienced in reaction to the challenge in this movie is exactly what you want to elicit in your readers. What this movie lacked, however, was an exciting action to keep me riveted throughout the story. Good action is the third ingredient of a story.

1.2.3. Action

To solve the challenge, the main character engages in action. The action is the central part of the story, the chain of events that constitutes the main narrative. Some of these events are predictable, while others surprise the readers. A good action keeps the readers on the edge of their seats and moves them to the point where they become emotionally invested in the story. For example, when a wolf enters the scene.

1.2.4. Climax

Most of the time, the action ends with a climax scene. The climax is the moment when everything falls into place. Secrets and misdeeds are uncovered, a key piece of information is revealed, or an unexpected twist occurs. The climax is an intense scene that captures the audience’s attention, usually because we are worried about the hero.

The climax is easy to identify in children’s tales: just look at the children’s reactions. As a child, I loved The Three Little Pigs. I had it on vinyl and asked my mother to play it over and over. But every time the wolf came down the chimney, I would scream in terror and beg my mum to stop the record. She told me this anecdote a while back, but it wasn’t until recently that I realized the chimney scene was the climax scene.

1.2.5. Resolution

At the end of the climax scene, the problem is solved: The detective has caught the murderer; the cool guy has snatched the pretty girl before she gets on the plane; the bad guy has died before the bomb exploded… All’s well that ends well. Now, all that’s left is to resolve and wrap up the story with a joke, a long kiss that promises love for eternity, or a comforting “Let’s go home!”.

For our three little pigs, the story finds resolution with a wolf stew and eternal happiness.

Am I the only one who feels sorry for this poor wolf?

Now in which way does storytelling relate to scientific writing?

1.3. Storytelling in scientific writing

Have you already guessed which part of a scientific paper corresponds to the five elements of a story described above? If you haven’t, please go back to the previous section and take a minute to think about it before reading the next paragraphs. That is the best way to engrave it in your memory.

1.3.1. Introduction

1.3.1.1. Research topic: The opening

The introduction to a scientific paper also begins with an opening on the characters and setting.

What is the character of a scientific article? Instead of the three little pigs, your main character is your research topic. It can be a disease, a molecule, a particle, a psychological construct, a chemical reaction, a material, a biological tissue, an economic transaction, a sociological phenomenon, a historical event… You name it!

What is the setting of a scientific article? The setting is the background information about the research topic that you provide in the introduction. The first few minutes of a story highlight the most iconic and compelling features of the character. Similarly, the first paragraph(s) of a scientific paper should explain why the research topic is important and what we already know about it. In scientific writing, this setting is called the niche. Your niche is the field of knowledge in which you place your research.

1.3.1.2. Research problem: The challenge

The research problem is the challenge of a scientific paper. After stating that your research is on topic X, explaining why it is important, and what one already knows about it, you must state the problem that the research intends to solve. A good story requires a compelling character facing a daunting challenge. Similarly, good research solves a relevant problem on an important topic. The topic and the research problem are the elements that create tension in your article and entice the reader to go on (if you’re asking yourself why I’m talking about a research problem rather than a research question, check this post).

Let me give you an example!

1.3.1.3. Example

Some time ago, I was giving a workshop at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, and I had a conversation with a student who understood perfectly how to communicate her story. That’s how she described her topic and research problem to me:

“20% of the food produced is wasted. Tons of perfectly good vegetables and fruits are thrown away because customers find them ugly. Yet, to this day, there is no method to encourage people to buy two-legged carrots and twisted cucumbers. My Ph.D. thesis aims to fill this gap by developing marketing strategies to make these products more appealing.”

I was shocked to learn that food waste was so severe and wanted to know more about her research. I could feel the tension that this pitch created in me.

In this research:

– the character / research topic is food waste

– the niche is the specific category of food waste called ugly products

– the challenge / research gap is the need for a strategy to get customers to buy these ugly products

Once you have defined the research problem in your introduction, you can announce the solution that you intend to bring to this problem, and wrap it up by stating the hypotheses and/or introducing the paradigm used to test them.

If you want to polish your introduction and make it a fine piece of writing, check out this post for more information and examples, and here to download your free template for the introduction.

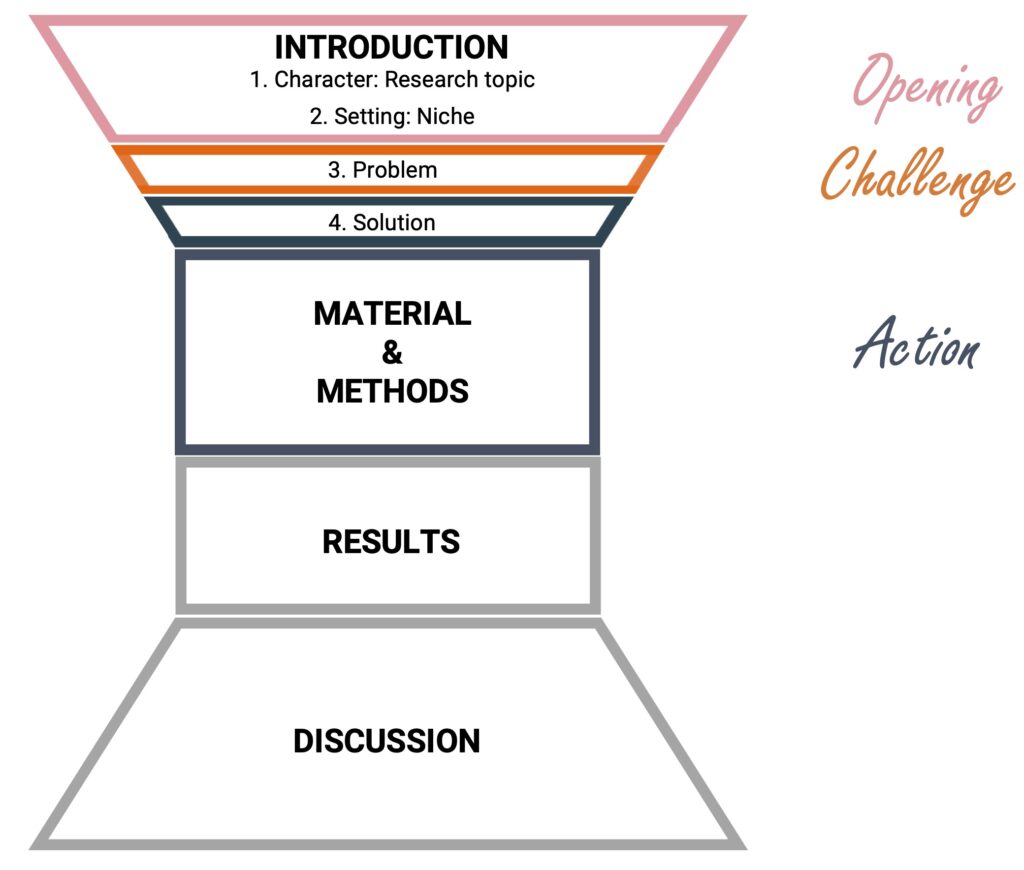

1.3.3. Material and methods: The action

The materials and methods form the action of your research. That’s how, we, scientists address the challenges we face: We conduct studies or experiments.

In a story, good action is characterized by the fact that the main character is completely taken up by the challenge. Similarly, in scientific writing, a good study focuses on solving the research problem. That’s the reason why you should identify your story early on in your research, actually before collecting any data.

I can’t tell you how many research projects I’ve been involved in where the researchers realized, as they were writing their paper, that the results would have been more conclusive if only they had measured other variables or designed their experiments differently. Many of these times, that researcher was me 🙂 Unfortunately, at that point, there was nothing I could do to change things. Now, when I start a new project, the first thing I do is write my story, and only then do I design my experiments.

There is no predefined structure for the methods section of a scientific paper, as it depends on the type of research you have performed. But if you are not sure how to structure your method section, I have a tip for you: Find two or three articles using a similar methodology and published in the journal where you intend to submit your paper; then, see how their method sections are organized. In 95% of the cases, you can adopt the same layout.

If you want to fine-tune the writing of your methods, check out this post. I have outlined the most important elements to keep in mind when drafting your methods.

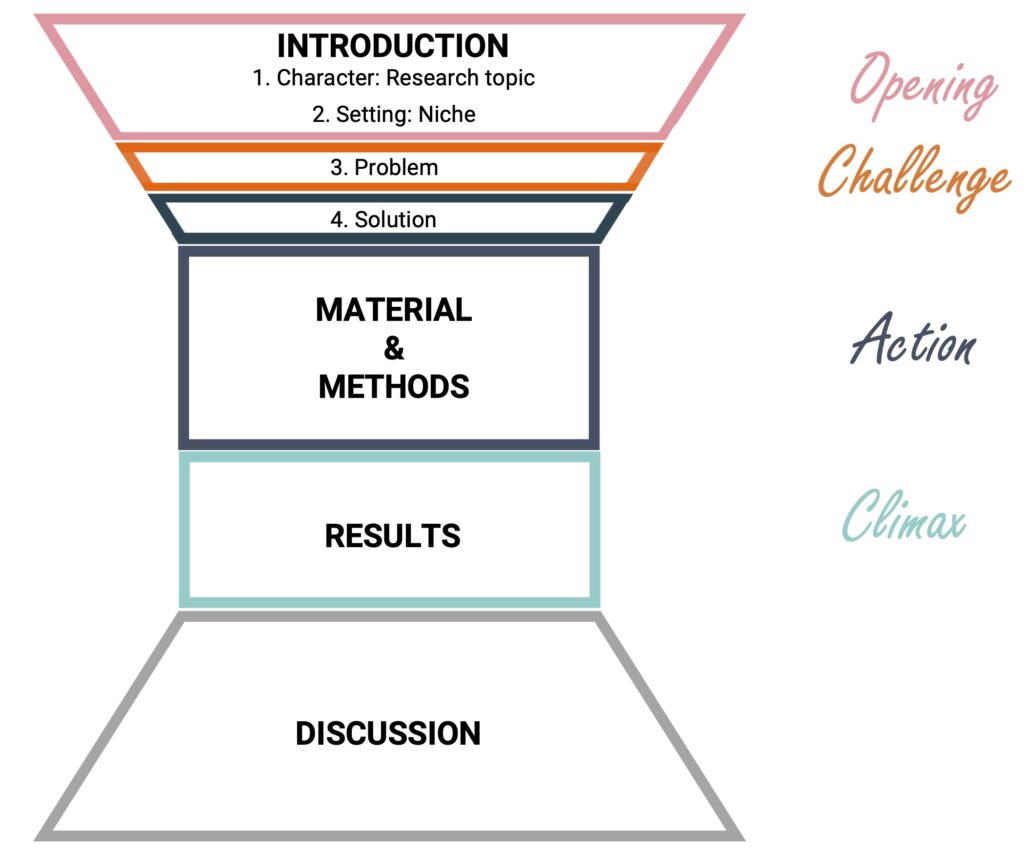

1.3.4. Climax: The results

The results of your study are the climax of your paper. That’s the moment when all the efforts you have put into the research come to fruition and when we finally learn whether the hypotheses are confirmed. And like all stories, the climax of a scientific project can elicit strong emotions.

Just as for the method section, the results section of a scientific article does not follow a predefined structure because it depends on the type of data you are reporting. Here again, if you are not sure how to structure your results section, I advise taking examples from similar articles published in the journal in which you want to submit your research.

Moreover, you can read this post to learn how to optimize your results section.

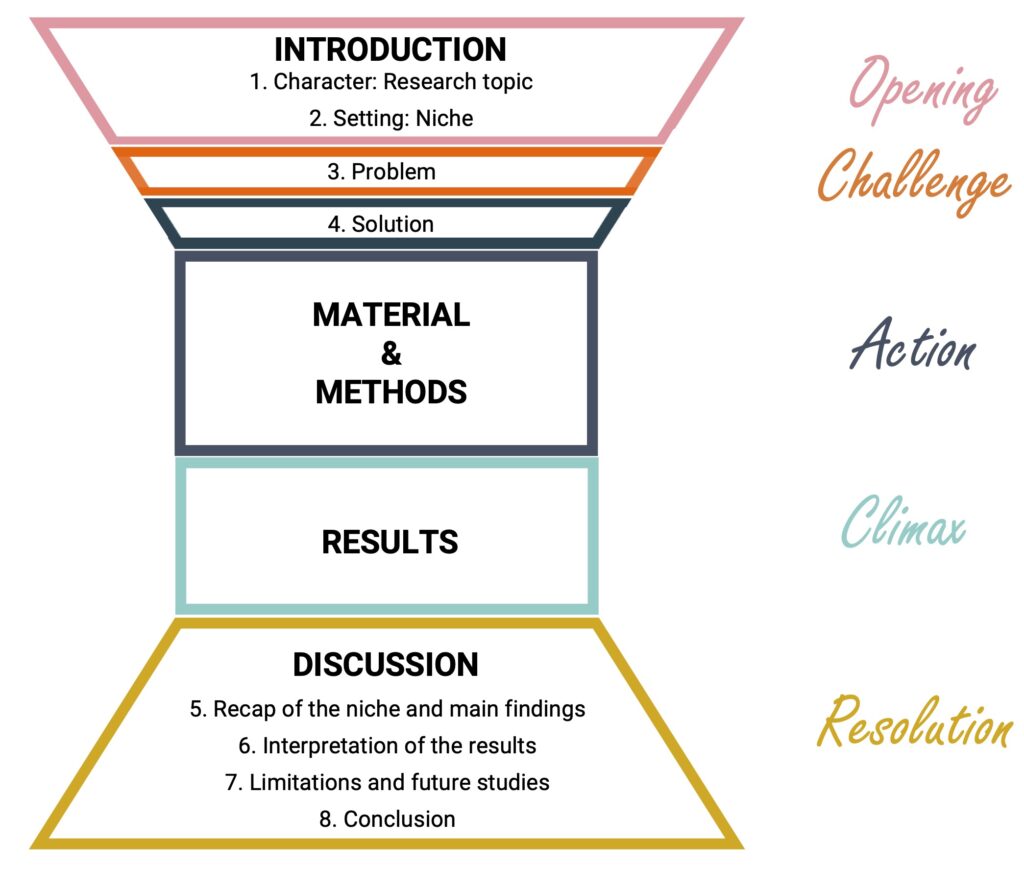

1.3.5. Resolution: The discussion

The discussion is the resolution of our scientific story. Now that we know what came out of this research, we can put the results in perspective with previous research and conclude.

The discussion is a mirror response to the introduction. It starts with a recap of the research niche and a summary of the main findings. Then, the results are interpreted in the light of previous studies. Indeed, you should explain how your results advance knowledge on the issue at hand, their limitations, and how future studies could address them. Finally, the article emphasizes the contribution of these results to the general research topic with which the introduction started and ends with a conclusion, i.e., a few sentences summarizing the take-home message.

To learn more about the discussion, go and have a look at this post.

1.3.6. Trailer: The abstract

Do you know these trailers that show the movie from beginning to end? Your abstract is that kind of trailer to your story. In cinema, I hate these trailers. If I’m going to see a movie, I don’t want to know everything that’s going to happen. But in a scientific article, it is useful to know the article’s main points before deciding to dive in.

The abstract of a paper contains the five elements of its story explained in few sentences. One sentence to introduce the characters/research topic, one sentence to describe the challenge/research problem, a couple of sentences for the action/methods, a couple of sentences for the climax/results, and one sentence for the resolution/conclusion*. It’s as simple as that!

(* Please note that I’m making a generalization here. The exact number of sentences depends on the maximum length allowed for your abstract).

2. Structure your paper

2.1. The IMRaD structure in scientific writing

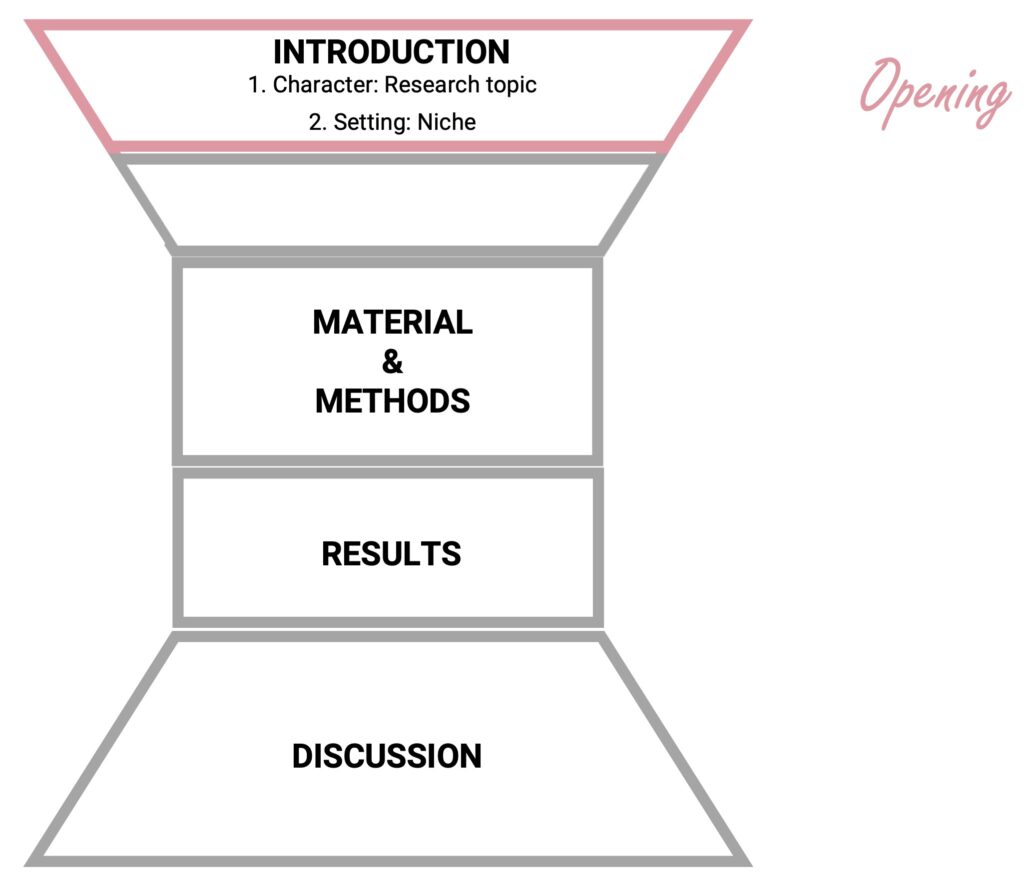

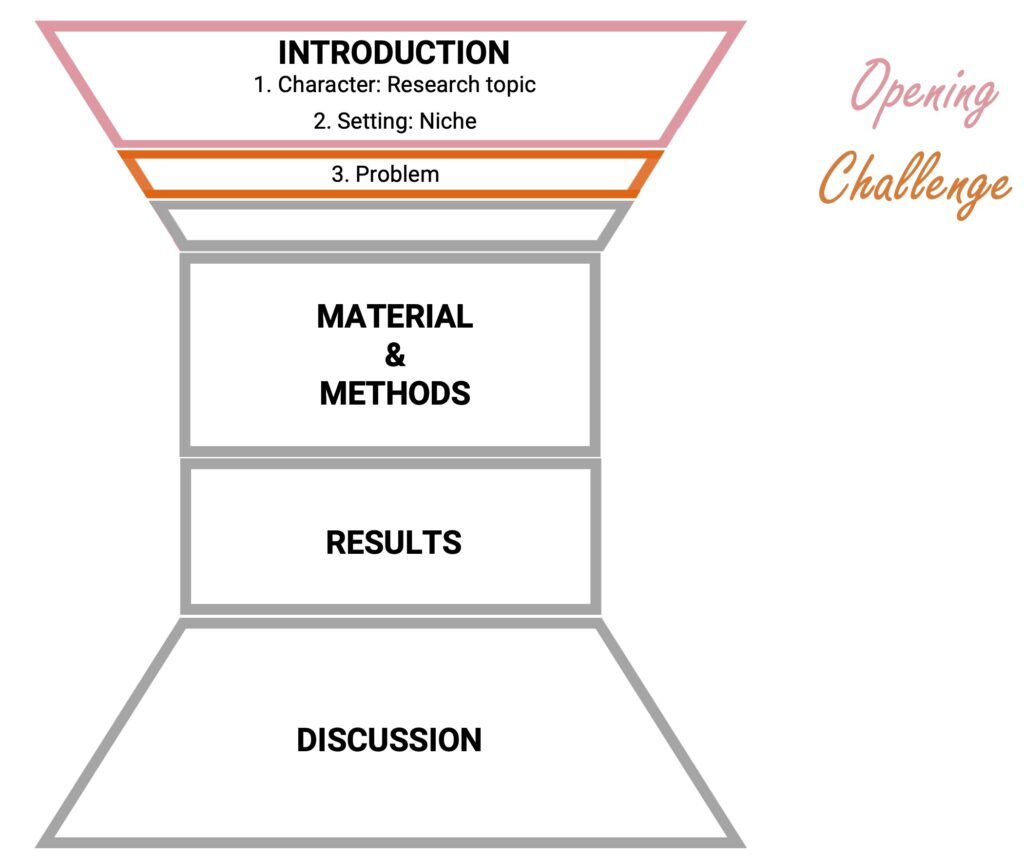

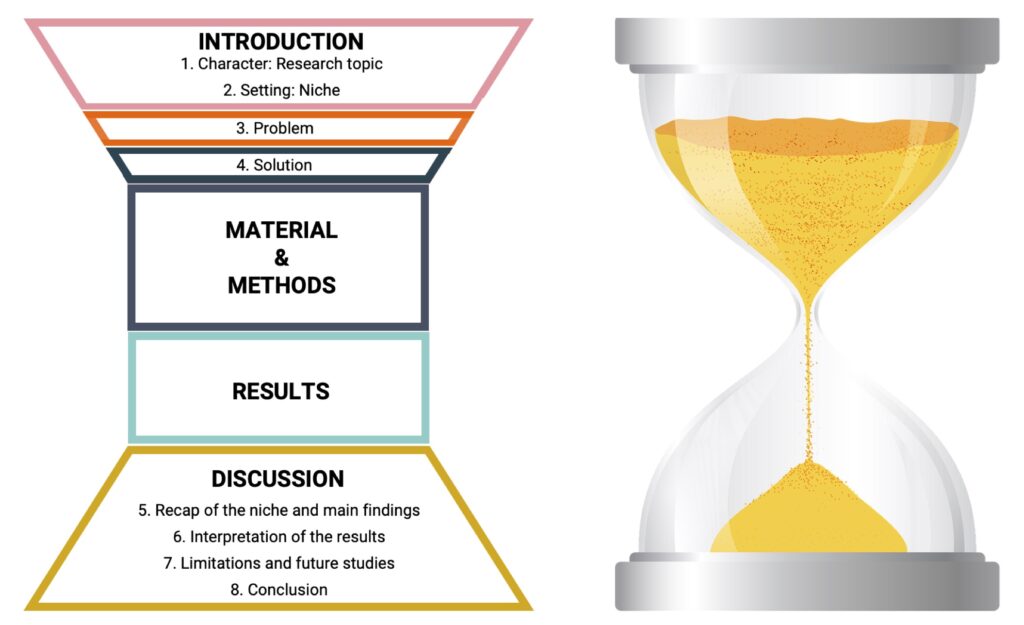

As you may have noticed from the previous sections of this guide, scientific articles tell stories following the IMRaD structure. IMRaD stands for:

– Introduction (sometimes also called Background)

– Material and methods

– Results

– and Discussion (and/or conclusion)

The IMRaD structure is the main template in scientific writing (you can find an example of an IMRaD paper published here). Usually, the four sections are presented in this order, but there are some exceptions.

Indeed, some journals require that you write the result section immediately after the introduction (e.g., in Nature). In that case, you briefly describe the experimental design at the end of the introduction or at the beginning of the results section and push back all methodological details to the end of the article before the reference list.

Other journals ask authors to combine results and discussion in a single section. This often happens for short articles, such as short reports. Articles that present several studies also sometimes use this format: Each study ends with a description of the results immediately followed by their discussion and a transition to the next study. In this latter case, you usually have a general discussion at the end of the article (see example here).

Even though the IMRaD structure may be subject to slight modifications here and there, you will always find it because it brings logic and symmetry to a scientific article.

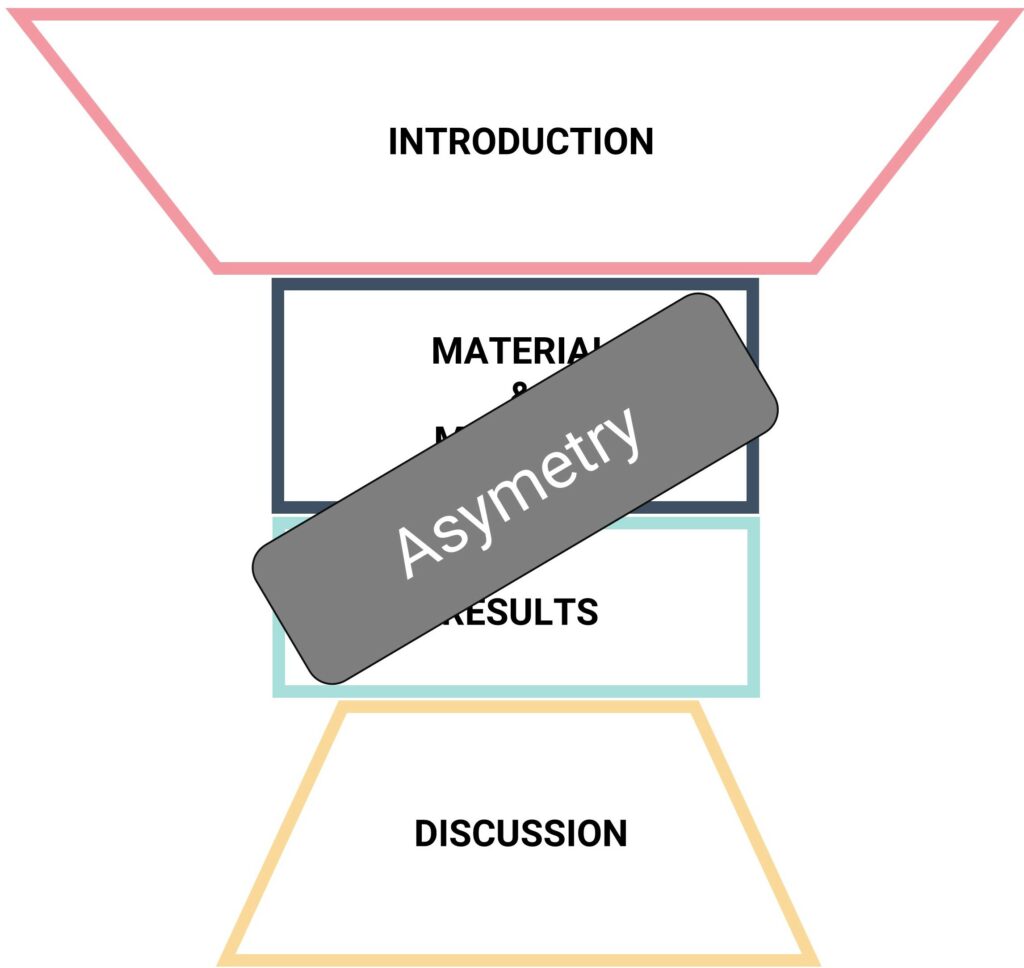

2.2. The shape of an hourglass

What has scientific writing to do with an hourglass?

Like an hourglass, scientific articles are wide at the beginning, narrow in the middle, and widen again at the end.

The top part of the hourglass is the introduction. The first few paragraphs of the introduction present the general topic of the research. But then, the article zooms in on the niche and the specific problem it aims to solve, ending narrowly by stating the hypotheses (if you have any) and/or introducing the methods.

The neck of the hourglass, i.e., the narrowest part, corresponds to the methods and results. These sections are specific, concrete, and descriptive, which explains why many scientists find them the easiest sections to write.

The lower part of the hourglass stands for the discussion. The discussion picks up where the introduction left off with a recap of the research problem and the main findings. Then it expands as the results are interpreted in light of existing research. Finally, the discussion ends with a conclusion that emphasizes the overall contribution of these results to the research topic. We end as we began: broadly.

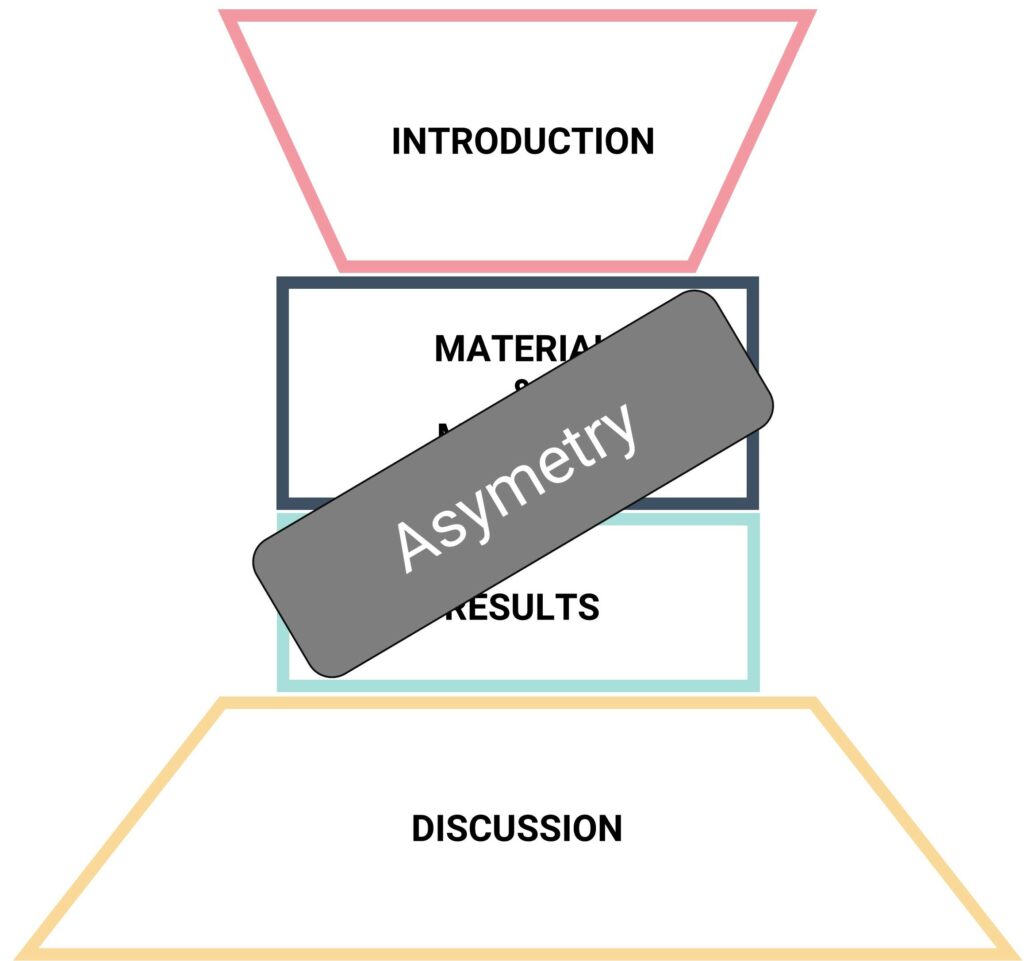

2.3. A symmetrical structure

In constructing your article, it is important to keep in mind that there must be symmetry between the introduction and the discussion. The introduction builds an expectation in the reader about the research topic and the problem it will address. The discussion is the mirror response to the introduction. Thus, if the article begins broadly, it should finish broadly.

If the opening is broader than the conclusion, the reader will have the feeling that the article didn’t deliver what it promised. Conversely, if the opening is narrower than the conclusion, the reader might not understand the logic that led to this conclusion. Matching the opening and conclusion satisfies the expectations of the reader and provides a feeling of closure to the paper.

How broad should your opening be? In general, it is wise to aim for a broad opening. The broader the opening, the more readers will be interested, and the more citations your article will get. However, the research should also satisfy the expectations that the opening triggers. Articles that overstate the importance of their contribution make disappointed readers (and reviewers). You should thus frame the opening as broadly as possible, given the conclusions that you can draw from the research.

Now that you have all the information you need to create the general structure of your paper, let’s go down one level: let’s talk about paragraphs!

3. Structure your paragraphs

Paragraphs are the unit of composition of your scientific article. They are the scenes in your movie: Just as the story of a movie goes from scene to scene, the story of a scientific paper moves from paragraph to paragraph.

In scientific writing, one paragraph expresses one idea, not more. This means that you can think of the number of paragraphs in your paper as the number of ideas you have to develop your argument.

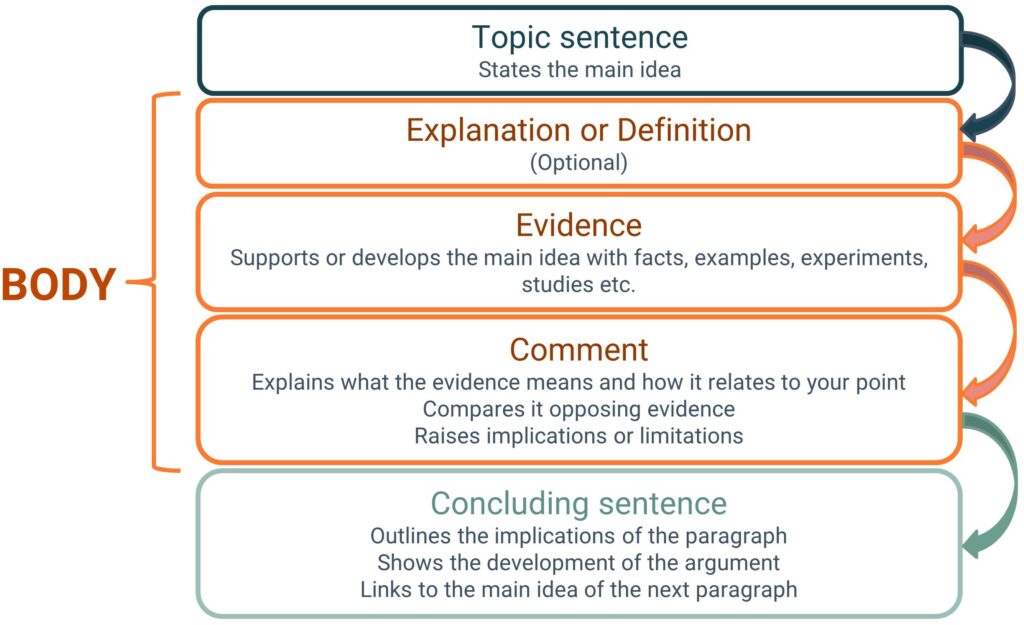

3.1. Paragraph structure

In scientific articles, paragraphs often follow a structure that makes the whole text easy to read. This structure entails 1) a topic sentence, 2) the body of the paragraph, and 3) a concluding sentence.

This paragraph structure is particularly useful for unfolding a narrative. As such, you will find it mostly in the introduction and discussion. You won’t necessarily need it for the materials and methods or the results sections, which generally use subheadings and don’t follow a narrative thread.

3.1.1. The topic sentence

Paragraphs often begin with the topic sentence, which states the paragraph’s main idea. An effective topic sentence notifies the readers of the subject that will be covered in the paragraph and incite them to keep reading.

The topic sentence should be general enough to encompass the general idea of the paragraph and relate to each of the sentences that constitute it. But it should also be specific enough for the reader to understand this idea and its relevance (an idea that is too vague is quickly banal and dull).

After stating the paragraph’s main idea in the first sentence, you move on to the body of the paragraph.

3.1.2. The body

The body of the paragraph can contain three types of information:

- Explanations or definitions: In some paragraphs, it is important to provide explanations or definitions to clarify for the reader certain concepts or acronyms.

- Evidence: Most of the time, a paragraph will include evidence to support the main idea that it puts forward. This evidence can consist of experiments, studies, facts, examples, or quotes.

- Comments: In scientific writing, you should also comment on the evidence or ideas you present. You may need to explain what this evidence means, how it relates to the point the paragraph is making, or you may want to compare it with other evidence, and raise implications or limitations.

3.1.3. The concluding sentence

Ending the paragraph with a concluding sentence makes the text easier to understand. The concluding sentence can take several forms:

- It can state the implications or consequences of the paragraph.

- It can also show the development of an argument. This can be particularly useful if you have described a complex chain of events in the paragraph (for example, a metabolic process in which a molecule undergoes several changes) and you want to summarise it before moving on to the next idea.

- It can also be a transitional sentence connecting the main idea of the current paragraph to the main idea of the next paragraph. Personally, I love ending my paragraphs with a link to the main idea of the next paragraph or a question that will be answered in the next paragraph. It works like a cliffhanger that encourages the reader to keep reading. You’ll find many examples of paragraphs finishing with a question or a transition to the next paragraph in this blog post. Go and try to look for them ;-).

Are my explanations of paragraph structure a tad abstract for you? Let’s take an example.

3.2. Example

I’ll give you an example from one of the first scientific papers published on COVID-19. This article was published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine in January 2020 to draw attention to a new virus that was about to change the lives of the entire planet. For a better reading, I have removed the bibliographic references, but if you are interested, you can find the original paper here. The paragraph below is the first paragraph of the introduction.

Topic sentence: Emerging and reemerging pathogens are global challenges for public health.

Body: Coronaviruses are enveloped RNA viruses that are distributed broadly among humans, other mammals, and birds and that cause respiratory, enteric, hepatic, and neurologic diseases (Definition). Six coronavirus species are known to cause human disease (Explanation). Four viruses — 229E, OC43, NL63, and HKU1 — are prevalent and typically cause common cold symptoms in immunocompetent individuals (Evidence). The two other strains — severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) — are zoonotic in origin and have been linked to sometimes fatal illness (Evidence). SARS-CoV was the causal agent of the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreaks in 2002 and 2003 in Guangdong Province, China (Evidence). MERS-CoV was the pathogen responsible for severe respiratory disease outbreaks in 2012 in the Middle East (Evidence).

Concluding sentence: Given the high prevalence and wide distribution of coronaviruses, the large genetic diversity and frequent recombination of their genomes, and increasing human-animal interface activities, novel coronaviruses are likely to emerge periodically in humans owing to frequent cross-species infections and occasional spillover events (implications of the paragraph).

To see how this paragraph structure applies to your field of research, pick your favorite scientific articles and try to identify whether the first few paragraphs of the introduction are structured in this way. Chances are that you will be able to spot at least the topic sentences.

4. Improve your style

Now that you have a great story, a great outline, and that your paragraphs are well structured, the last thing you need to do is work on your style. By style, I mean the way you express yourself and make your explanations understandable to the readers.

You can find countless books and tips on how to improve your style. Since I like to keep things simple and effective, I focus on four elements that tremendously improve the readability of my articles without burning me out. Here they are!

4.1. Declutter

Clutter refers to any words, phrases, or paragraphs in your paper that are not essential or that make reading unnecessarily arduous. Decluttering means simplifying as much as possible.

To simplify your style, I recommend focusing on three forms of clutter: complex expressions and jargon, adverbs and adjectives, and little qualifiers.

4.1.1. Avoid complex expressions and jargon

I suspect that scientists like complex expressions and jargon because they believe it makes them sound smart. It’s a mistake. No fancy word can replace an ingenious idea or a sound argument. Our mission as scientists is not to sound smart; it is to be smart and to communicate our ideas as clearly as possible. Complex expressions and unnecessary jargon do the opposite: They complicate your text for no good reason.

The verb utilize is a good example of a complex and jargonous word. This verb has become a trend in scientific writing. Utilize is misused in 99% of the cases (yes, I just made up this number :-). Indeed, utilize means using an object for purposes other than those for which it was designed. For example, you would utilize a shoe to drive a nail into the wall because you don’t have a hammer at your disposal. However, in your research, when you use a method to test precisely what it was designed to test, then you didn’t utilize it; you used it. That’s good enough!

4.1.2. Remove adverbs and adjectives that do not add meaning

Adverbs and adjectives are other common forms of clutter because they often have the same meaning as the verb or noun to which they are attached. Does it seem abstract to you? Let’s take a few examples from published articles.

People can learn by simply watching others successfully master the task.

Can one unsuccessfully master a task? I have to admit that I found this example in one of my articles. Ah! the things you find when you start looking…

Social comparisons are deeply rooted in the human psyche.

Isn’t the idea of a root to be deep? Another example found in one of my papers :-).

The current article presents a new discovery.

As opposed to what? A discovery that everyone already knows?

We implemented a practical intervention to support young people at risk.

An intervention is inherently practical, isn’t it?

We disagree with the authors’ interpretation, as well as their final conclusion.

I’m curious what their starting conclusions were :-).

Again, I suspect we add all this clutter to emphasize our point. But the opposite happens. Like too much makeup hides the beauty of a pretty woman, too many adverbs and adjectives weaken your message.

4.1.3. Avoid little qualifiers

Little qualifiers are words that limit or enhance an adjective, such as very, in a sense, little, really, basically or sort of. They signal a lack of confidence on your part and thus weaken your style and persuasiveness. An American friend told me that she learned to never write very in an academic paper. This anecdote stuck with me, and since hearing it, I have developed an allergy to the word very.

In most cases, you can remove little qualifiers, adjectives, and adverbs from your text.

Chemotherapy is basically one of the most efficient treatments for cancer.

Better: Chemotherapy is one of the most efficient treatments for cancer.

What if you want to use a little qualifier to emphasize or moderate an adjective? The solution is to find a synonym for that adjective that expresses exactly what you mean, such as:

Social learning theory has played a very important role in developmental psychology.

Better: Social learning theory has played a central role in developmental psychology.

This result is terribly surprising.

Better: This result is shocking.

The animals carried a really small detector attached to their leg.

Better: The animals carried a tiny detector attached to their leg.

Using precise vocabulary and concise wording makes your writing compelling.

4.2. Kill your darlings

Stephen King has written an excellent book called On writing in which he describes his writing process and provides countless tips to improve one’s style. My favorite tip is that to write with impact, you must kill your darlings. In scientific writing, your darlings are words, phrases, paragraphs, or ideas that excite you but don’t add meaning or push your story forward. Recently, I had to perform such slaughter on one of my texts.

Indeed, a few months ago, I submitted a grant proposal to the Austrian Science Foundation, and I was struggling with my outline. I loved one paragraph, but I didn’t know what to do with it. I tried to move it around, break it up into several sections, rewrite it. Nothing worked! Then I realized it was one of my darlings. This paragraph described a theory that fascinates me, but I didn’t need this theory to explain my project. It was more confusing than anything else. I thought of Stephen (in my fantasy, he and I are on a first-name basis), and I realized I had to kill it (the paragraph, not Stephen). I deleted that paragraph, and the whole story fell into place.

If you have trouble with a sentence or paragraph, ask yourself what would happen if you deleted it. Would it still be understandable? Would your argument even be more straightforward? If the answer is yes, you know what you need to do.

4.3. Use the active voice

I am pretty sure that you’ve already heard about active and passive voices, but I will give you an example to refresh your memory.

Active voice: The experimenter brought the participants to the lab.

Passive voice: Participants were brought by the experimenter to the lab.

For a reader, the passive voice is more difficult to understand than the active voice. So, when possible, it’s best to avoid it. It does not mean that you should never use the passive voice; it means that you should restrict it to situations where it is appropriate.

The passive voice is appropriate when you want to draw attention to the person or thing affected by the action. In the example above, if you intend to focus on the participants and describe the procedure from their point of view, it may make sense to use the passive voice. But if you are describing the different steps that the experimenter took, using the passive voice is pointless.

How much passive voice is acceptable? Writing pluggins recommend staying below 10% of the sentences. However, I find that in scientific writing, you can give yourself a little more leeway, especially in the methods and results sections. Still, I would advise you to stay below 15% of passive sentences.

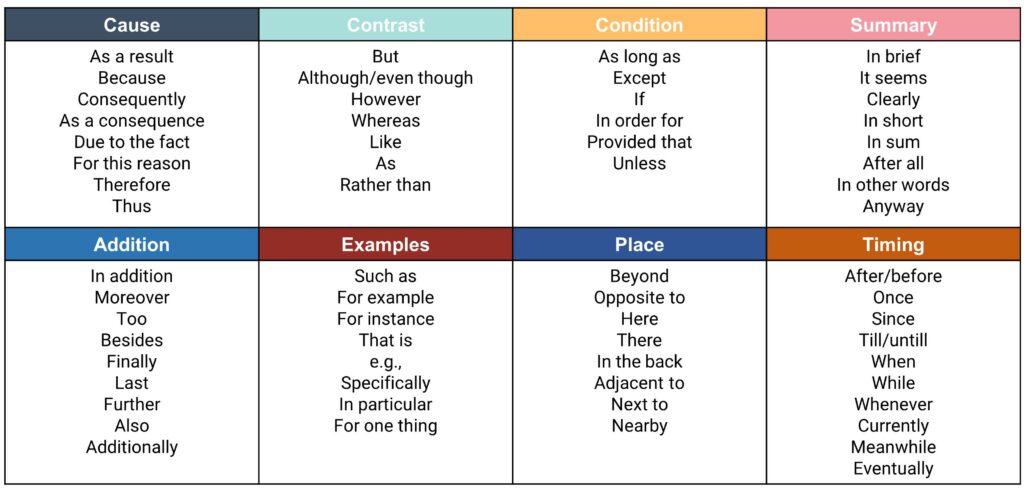

4.4. Use conjunctions

Conjunctions are words or phrases that link words, clauses, or sentences.

Conjunctions are useful because they help the reader understand the relationships between different ideas or statements. For example, you can use conjunctions:

- To show a causal relationship: The solution containing the tested element was black, so we incorporated additional color correction fabrics into the test procedure.

- To emphasize the contrast between two elements: Previous research suggests that the prefrontal cortex plays a central role in decision making; however, our results do not replicate this finding.

- Or to indicate the conditions under which a specific effect occurs: International companies are free to advertise their products, provided they comply with European regulations.

Feel free to use the table below as an inspiration to add conjunctions to your paper.

5. Conclusion

Thanks for having stayed with me throughout this ultimate guide on scientific writing!

Scientific writing is one of the most useful skills for a scientist. It enables you to communicate clearly your ideas and research to the world. I hope that I have also convinced you that being a skilled scientific writer makes you a better researcher. In this post, you have everything you need to craft excellent papers starting with the more general elements of storytelling and article structure to finish with the more specific characteristics of paragraph structure and style.

I know that writing your paper is a lot of work and can feel overwhelming at times. To help you get started, I have created a template of the introduction. This template is easy to use, much like a cooking recipe: You just need to answer a few questions and tada! you have the first draft of your introduction. To receive this template click here.

I wish you the best of luck in your scientific writing journey and look forward to reading your papers in the best journals

Gaya

Pingback: How to structure the introduction of your article - A Brilliant Mind

Very nice write-up. I absolutely love this site.

Keep writing!

Pingback: How to write the method section of your article - A Brilliant Mind

Pingback: How to structure your scientific article (Part 4: The result section) - A Brilliant Mind

Pingback: How to structure your scientific paper (Part 5: The discussion) - A Brilliant Mind

Pingback: How to structure your scientific article (Part 3: The method section) - A Brilliant Mind

Pingback: How to write the introduction of your scientific paper

So helpful and informative. Everything I need in a nutshell!

Thanks, Mina! I wish you good luck in your writing journey!

Pingback: How to write the introduction of your scientific paper

Pingback: How to structure the discussion of your scientific paper : A Brilliant Mind

Pingback: How to structure the result section of your scientific article : A Brilliant Mind

Pingback: 5 books on writing every scientist should read : A Brilliant Mind

Excellent piece you have here, Gayannée. Looking forward toward to partnering with you in writing and publishing scientific articles.. I am an early researcher, just budding. Wouldn’t mind associating with your extremely brilliant mind.

Shalom and Blessings.

Thanks a lot, Wisdom!

Very excellent, and commendable approach to guide a beginner in scientific writing. Please, I need a soft copy of this write-up. Thanks

Dear Abdulaziz,

Thanks for your kind words!

Unfortunately, I don’t have a hard copy of the guide but you can always find it online. You can also download my writing kit, which includes a template to use as the draft of your paper and step-by-step instructions to write your introduction. You can find this kit at https://abrilliantmind.blog/contact-gayannee-kedia/

Good luck with your writing!

Gaya

Pingback: The opening of your paper: The Indiana Jones method : A Brilliant Mind