Scientific abstracts are of huge significance within academia. Whether they accompany a doctoral dissertation, a conference presentation, or a journal article, abstracts serve as the readers’ initial—and often only—encounter with your work. They create the first impression of your research, encouraging readers to explore the rest of the article or attend your presentation. Unfortunately, most scientific abstracts tend to be as captivating as the ingredients list on a box of Cheerios.

In this blog post, you’ll discover what makes a good scientific abstract. We’ll look at nine key elements of excellent abstracts. And at the end of this post, I share a free checklist to ensure your abstract incorporates these critical elements and maximizes its impact.

Shall we get started?

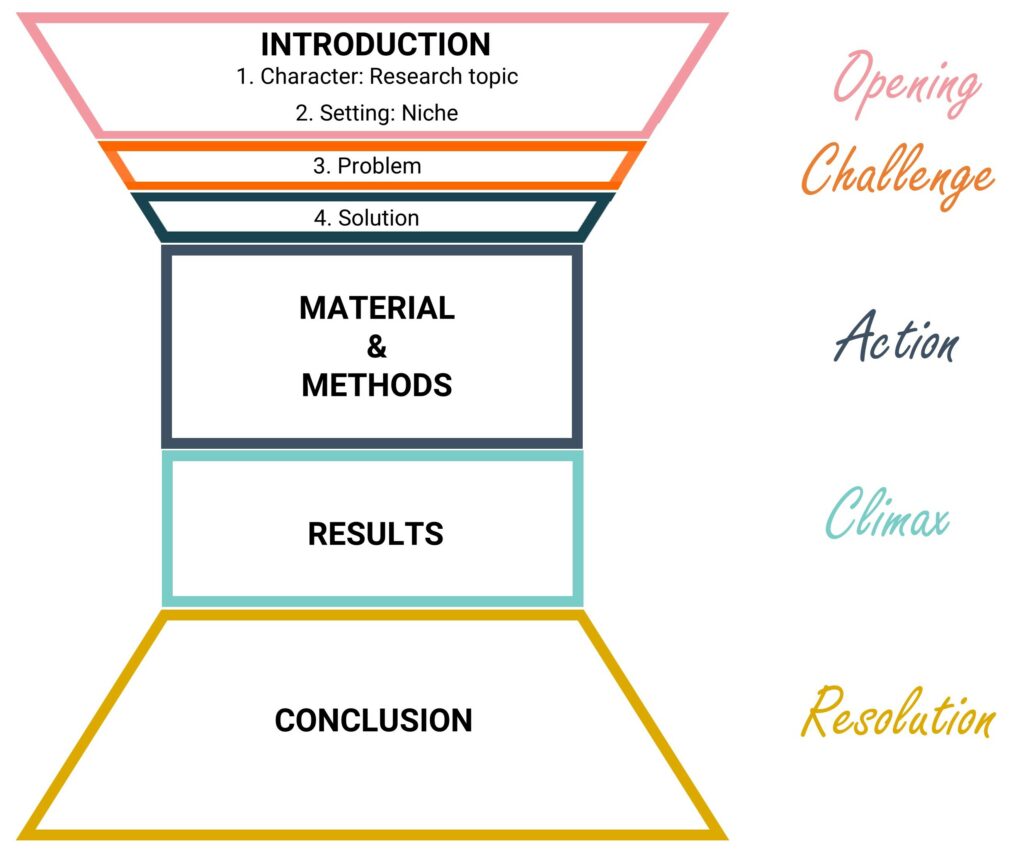

1. A good scientific abstract tells a story

The abstract is to your article what a trailer is to a film: a condensed version of its story. Like all stories, your abstract should encompass 5 elements (check this post for more information about storytelling):

- An opening: Initiate your abstract by introducing the character of your story – your research topic. Your research topic is the one thing that the research advances. It could be a protein, a disease, a chemical, a reaction, a gene, or a psychological function. To captivate your readers right from the start, start your abstract by explaining why your research topic is important.

- A challenge: Your abstract should then depict a challenge – the problem your research aims to solve. Pointing out the problem creates tension in your readers and emphasizes the importance of your research. So, don’t hesitate to poke the knife in the wound and explicitly state why the world wasn’t a good place until you did your research.

- An action: In the third segment of your abstract, describe the action you undertook to overcome the challenge, i.e., your methods.

- A climax: Next, present the climax of your story, i.e., the main results of your research.

- A resolution: Lastly, round off your story with a resolution explaining how your results solve the problem and contribute to the broader research topic you started your abstract with.

Write one or two sentences for each element, et voilà! You have your abstract.

Do you worry that you may struggle to keep track of all these elements? Click here for my free abstract checklist!

2. A good abstract focuses on the most central results

A terrible sin sometimes occurs in scientific abstracts when authors focus on results peripheral to the research. This can happen when the study results do not validate the main hypotheses, but some other effect, not necessarily expected, turns out to be significant. Authors may then try to “sell their study” by focusing on the significant results and omitting those that are not. In general, this strategy does not work.

An experiment designed to test one hypothesis is rarely suitable for testing another. If you try to change your story after the fact, your readers will be able to tell that you are trying to hide something, or they will be confused because some elements of your design do not make sense. This is bad research practice, and a reviewer may reject your paper for that.

Be honest. Focus on your most central findings and what you learned from them. If you have reviewed the literature correctly before creating your study and if your methods are sound, your results ARE interesting, even if they are not what you expected.

3. A good abstract follow the guidelines given by the journal or conference

Journals or conferences provide guidelines for writing scientific abstracts, starting with a word or character limit. This limit is usually between 150 and 250 words.

For many scientists, summarizing years of work in a few sentences is a real pain in the neck. Unfortunately, you must respect the word count. There is no way around it, as most journals and conferences require you to paste your abstract into a box on the website that counts characters. So, to avoid last-minute stress, follow the guidelines from the start.

Important point: To meet the length requirements, many scientists sacrifice one or several of the story elements. Usually, they skip the introduction (character and challenge) and the conclusion (resolution) to have more room for the methods and results. Please don’t do this: Cutting out your story weakens your message. A trailer that only shows the action scenes and fails to introduce the main protagonist won’t hook the audience. If you must be concise, keep one sentence for each element and focus on the most important results. No one expects you to be exhaustive in an abstract.

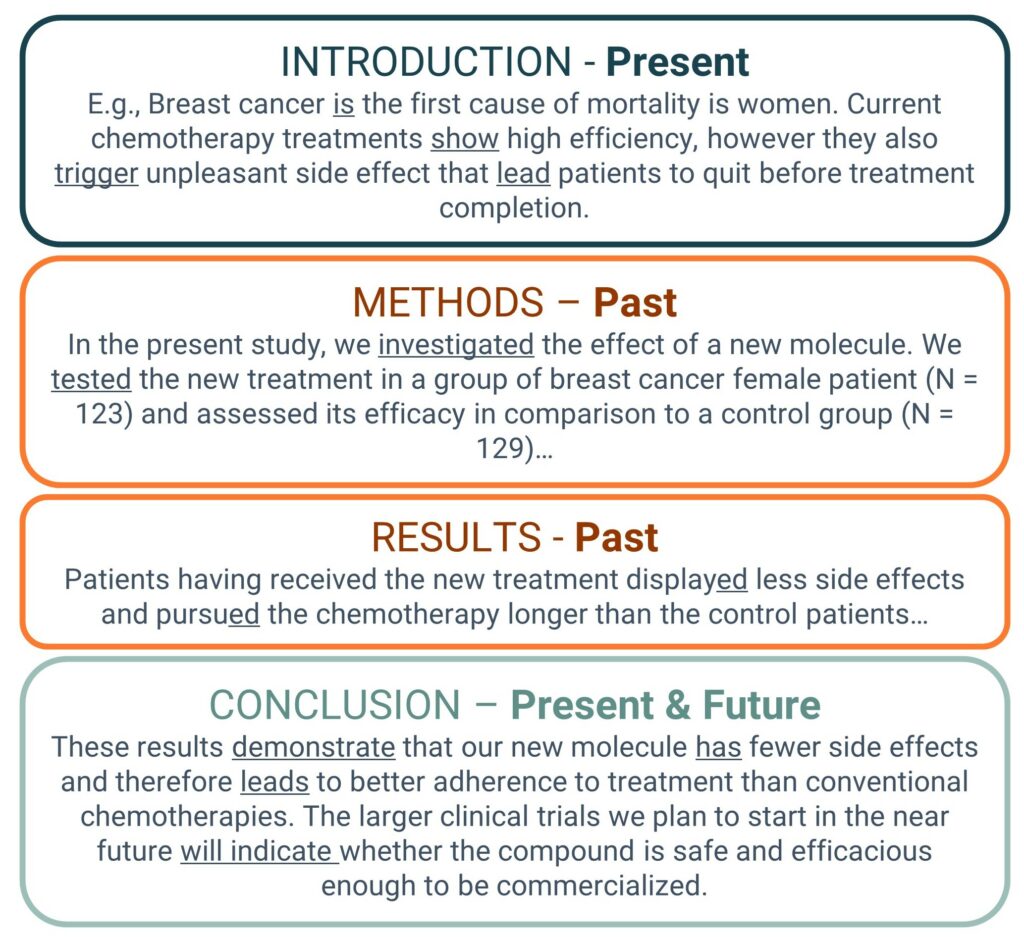

4. A good scientific abstract is written in the appropriate tenses

Each element of the story should be told in a specific tense, namely:

- Present tense for the opening and challenge (i.e., introductory sentences)

- Past tense for the action and climax (i.e., description of methods and results)

- Present or future tense for the resolution (i.e., concluding sentences)

Here is an example.

5. A good scientific abstract contains the main keywords

Researchers and professionals in your field will look for papers in databases by entering specific keywords. If these keywords are present in your abstract, the chances that they will find your article are higher. Therefore, before writing your abstract, identify the most important keywords and include them in your abstract.

6. A good scientific abstract doesn’t entail any cliché

Many abstracts contain standard phrases, such as:

- “X is one of the most central mechanisms.”

- “The implications of this research are discussed.”

- “These results have clinical applications for the field.”

These clichés do not provide relevant information to readers; they waste their time and your word count. So, delete them and replace them with precise statements describing what makes X important or the implications or applications of your research.

7. A good abstract entails no (or few) abbreviations

In general, you should keep the abbreviations in your abstract (and in your paper) to a minimum. Indeed, abbreviations are indigestible and put off readers who are not specialists in the subject. But there are some exceptions.

In some cases, using an abbreviation in a scientific abstract is fine. For example, certain methodological terms (e.g., fMRI) or molecules (e.g., DNA) must be abbreviated because that’s how we know them. If everybody knows what they mean, you may not even have to define them.

If a term with a lengthy name, such as a molecule or a gene, is used several times in a summary, it may be a good idea to abbreviate it. You then define it the first time and use the abbreviation for subsequent repetitions. [But remember that you will have to define it again in the main article; the definition in the abstract is not enough.]

In any case, check the journal guidelines before you finalize your abstract. Many of them have instructions regarding abbreviations.

8. A good abstract can reuse some of the article sentences

Young researchers often think they have to write original sentences in their abstracts and go to great lengths to rephrase ideas they have already formulated in other sections of their papers. I don’t think that it is necessary. I have never read a guideline that says the abstract must contain only novel sentences, and I know prominent researchers who copy and paste sentences from their articles in the abstract. So, if it’s easier for you, go for it!

Reusing sentences from your paper in your abstract is not plagiarism. Usually, no one notices it unless you repeat the first sentence of the introduction (and I would advise against doing that).

9. A good scientific abstract is well written

Don’t hesitate to polish the style of your abstract. Most readers will start your article by reading its abstract, so it needs to make a good impression. How can you do this?

- Start by removing all words that don’t add meaning, such as unnecessary adjectives and adverbs.

- Rephrase passive sentences into active ones.

- Add conjunctions.

- Ensure that a lay audience can understand it (this advice is especially relevant if you intend to publish your paper in a generalist journal).

Applying these four actions to the whole paper is a lot of work, but it only takes a few minutes for an abstract. And it’s the best way to learn and make these rules your own. See here for more style tips.

In sum

Crafting an effective scientific abstract is more complicated than it looks. It involves a balance of clarity, precision, and strategic focus. Following the nine tips described in this post, you can create abstracts that accurately represent your work and engage your readers.

To help you put all these tips into practice, I have prepared an Abstract Checklist. It’s a simple tool to ensure you haven’t missed any crucial elements while crafting your scientific abstract. Pick one of your abstracts and put it through this checklist. This direct comparison will immediately reveal any missing elements and guide you in refining your abstract to its best version.